[ad_1]

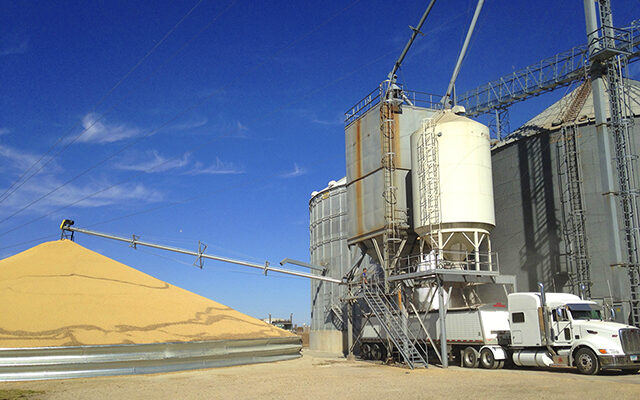

In mid-September, the computer systems of Crystal Valley, a farm supply co-op in Mankato, were frozen by a cyberattack. The company went from digitally tracking payments for fuel and grain to having to use paper tickets. Around the same time, two Iowa farm co-ops were also attacked.

“Customers and business partners alike should assume that their personal information was compromised,” Crystal Valley said in a statement.

The breach adds to the growing list of cyberattacks on U.S. infrastructure and companies this year, from the Colonial Pipeline, the largest gas pipeline in the country, to meatpacking factories for JBS, the world’s leading meat producer. But security experts say that agriculture and food businesses are at distinct risk of being hacked due to years of increasing reliance technology while overlooking cybersecurity.

Minnesota’s agriculture industry is taking notice. The state is fifth in the nation for total agriculture production and hosts powerhouse food companies like General Mills and Cargill. At best, a cyberattack could cost millions of dollars, cause food shortages and drive up prices. At worst, it could contaminate food and harm consumers.

“The concern is high, and the questions about what to do about it are significant,” said Tamara Nelsen, executive director of AgriGrowth, a nonprofit organization representing Minnesota agriculture.

Tamara Nelsen

But increasing security isn’t easy. Challenges range from the industry’s reliance on old technology to a lack of strong cybersecurity education. “It’s not a sexy topic,” said Kevin Paap, president of the Minnesota Farm Bureau Federation. “Especially those that are less technology oriented …. It’s like anything in life, people will never support something they don’t understand or can’t explain to others.”

A lack of focus on security

Cyberattacks have been an issue since the 1990s, though back then “nobody talked about it,” said John Hoffman, senior research fellow at the Food Defense and Protection Institute. “Companies didn’t realize they’d been broken into until months, sometimes years later.”

Since then, attacks have evolved from espionage to being destructive. Now, one of the most common cyberattacks is a ransomware attack, so named because after stealing data, hackers freeze computer systems by encrypting them and demand a ransom payment to give the data back.

Kevin Paap

Even if the ransom is paid, hacked computers need to be replaced. Rebuilding company infrastructure takes time and money, slowing down business.

In some ways, fighting cyberattacks is a losing battle. Many attacks are state-sponsored, meaning that the groups carrying them out are supported by countries like Russia and China.

“You got a lot of young, very talented programmers over there that have been brought along by these people who have basically…unlimited resources,” Hoffman said. “Companies are being targeted with scale capabilities that are enormous, much greater computing power than the company has.”

And while the threat has grown, so has agriculture’s reliance on computers to increase production.

“These are machines that are built to do a very specific thing. It might be… a camera watching product coming off a line or a robot that’s making boxes,” Noah Korba, General Mills’ director of cybersecurity said at a cybersecurity panel at AgriGrowth’s Nov. 4 summit. When installing this tech, “even 10 years ago, cybersecurity just wasn’t something people were thinking about.”

Many production lines run on outdated software, like Windows 98 or early versions of Linux, that have been attended to with an “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” attitude. Now they are an expensive liability to fix.

Part of the reason the agriculture industry spent years ignoring cybersecurity is lack of federal action. There are no mandatory cybersecurity requirements for any of the country’s critical industries. As a result, “from a management standpoint, this was not seen as a priority,” Hoffman said.

Plugging the holes

Experts say there are basic steps that any agriculture business, no matter how large or small, can take to guard against attack. Workers should keep all devices, from production line computers to GPS-enabled tractors, disconnected from the internet unless there’s a software update, and need to keep regular back-ups so that if there is an attack it’s easier to restore computer systems. And companies should train all staff in what Korba calls “personal cybersecurity hygiene,” like using multi-factor authentication and password managers to make it hard for hackers to break in using an employee’s stolen password.

“It’s that old adage of the bear,” Korba said. “You don’t have to be the fastest person, you just have to be the second slowest person” to survive.

But increasing security is a hassle. Particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, agriculture businesses got used to keeping computers connected to the internet at all times so that workers can check on production from home. And keeping track of security can slow down the workflows that people are used to.

“We need to break that convenience cycle,” Hoffman said. “We got to begin to balance security against convenience.”

Federal agencies like the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and the Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), offer resources to train employees and secure businesses against cyberattacks.

“Our tax dollars are paying for those resources to help individuals, small businesses, larger businesses, stay safe,” Nelsen, of AgriGrowth, said. But she noted a lack of federal or state grant programs to financially support industry security.

“I haven’t seen any, in fact,” Nelsen said. “That was going to be one of my questions…to the Department of [Agriculture] and maybe to the state or to the Chamber of Commerce just to say, ‘Can we apply for some federal grants to maybe do some pilot projects in agriculture?’”

Just like the industry, though, the state may have a lot of catching up to do. When reached for comment on cybersecurity issues, a spokesperson for the Minnesota Department of Agriculture replied in an email: “We don’t have IT experts or cyber security experts on our staff or that would focus specifically on cyber security in the agriculture industry.”

[ad_2]

Source link